Ashkenazi cuisine

Ashkenazi cuisine is mainly the cuisine of Jews from East-Central Europe even though it originated in Medieval Germany and France.

Developed in a cool climate, Ashkenazi cuisine is based on rich and fatty products. Its main ingredients are: grains (rye, barley, buckwheat, wheat), fish—especially herring and freshwater fish, beef and poultry as well as locally available vegetables (onion, carrot, cabbage, cucumber, beetroot, potato), and fruits (apples, pears, plums and berries).

Developed in a cool climate, Ashkenazi cuisine is based on rich and fatty products. Its main ingredients are: grains (rye, barley, buckwheat, wheat), fish—especially herring and freshwater fish, beef and poultry as well as locally available vegetables (onion, carrot, cabbage, cucumber, beetroot, potato), and fruits (apples, pears, plums and berries).

The main fats were goose or chicken fat. Garlic, horseradish, parsley, dill, caraway seeds, and pickles added flavor. The meals were prepared over a long time and most often served hot, soft, oily and delicate.

Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews (Heb. "Ashkenaz"—biblical ruler whose kingdom allegedly covered Northern and Central Europe) – Jews who in the Middle Ages settled in Western, Central and Eastern Europe. In the 10th-12th centuries, the centre of their culture was in the German lands; from the15th century onward their settlement shifted to the East, particularly to the territory of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Ashkenazi Jews spoke Yiddish, a fusion of medieval western Germanic dialects, Hebrew and Aramaic, and eventually also Slavic.

Polychrome on a vault of the synagogue in Gwoździec

Present-day Ukraine, second half of the 17th c.-18th c.; reconstruction

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews

Germany – the cradle of the Ashkenazi diaspora

Just like their Christian neighbours, Jews residing in Medieval Germany used to eat substantial meals—such as nourishing thick soups, cereal, meat, fish, root vegetables and leafy greens—to which they added lots of onion and garlic. It was in Germany that the main culinary tradition of Ashkenazi Jews was born: braided challah, gefilte fish, chopped liver, stuffed goose neck, chicken soup with noodles, cholent and kugel.

IN MEDIEVAL EUROPE

Hanna Zaremska, historian and medievalist, talks about living conditions of Jews in the Middle Ages and how they made an impact on Jewish culinary culture.

"Simchat Torah at a synagogue in Livorno"

Salomon Alexander Hart, 1858. The painting shows Sephardi Jews at a synagogue. In Italian towns and cities, Sephardi synagogues functioned side by side Ashkenazi ones.

Wikimedia Commons

Italy – an intersection of cultures

Italy was home to three Jewish communities: Jews who had been living in Italy since antiquity, Ashkenazim, and Sephardi Jews who arrived later. Since Italian Jews were mobile and engaged in international trade, their cuisine was inspired by many different cultures and was regionally diverse.

As early as the Middle Ages, Jews from Italy brought noodles to Germany, called "lokshn" in Yiddish.

As early as the Middle Ages, Jews from Italy brought noodles to Germany, called "lokshn" in Yiddish.

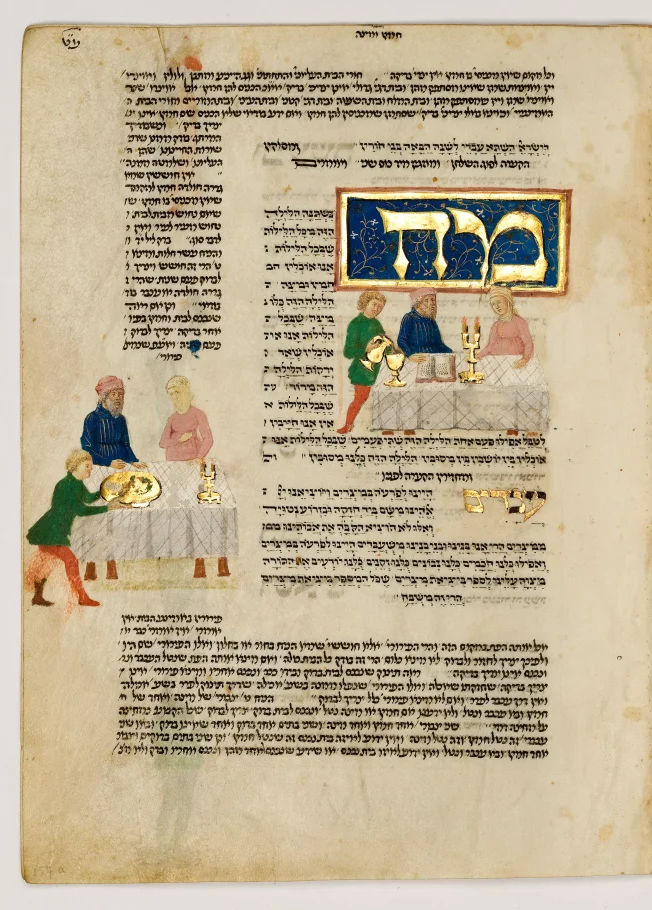

Seder dinner

Illustrations in co called Rotschild Miscellaneum (a collection of varia), Venice, 1470

The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

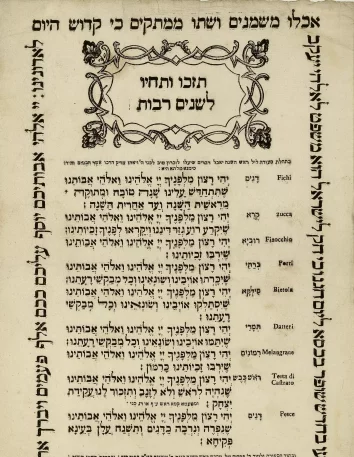

Blessings of food consumed on Rosh Hashanah

Printed card to be hung in the kitchen, Livorno (?), c. 1800

Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv

Poland and Lithuania – sweet and peppery

Ashkenazi Jews started to move further east in the 12th-13th centuries, bringing with them culinary traditions which had developed in Germany. By the 16th and 18th centuries today’s Poland, Lithuania, Ukraine and Belarus became the heart of the Ashkenazi diaspora. New ingredients and dishes appeared along with this change, such as heavy black breads, pickled cucumbers, horseradish, cottage cheese, sour cream, and barley. Other dishes such as borscht, blintzes (pancakes), farfel (kind of noodles), kreplach (dumplings), gribenes (cracklings), fruit compote, knishes and bagels reflected local influences and grew increasingly popular. Residents of various regions of this vast territory developed different tastes. In the Polish lands, sweet tastes dominated, whereas in the Lithuanian territory salty and peppery flavours were more common.

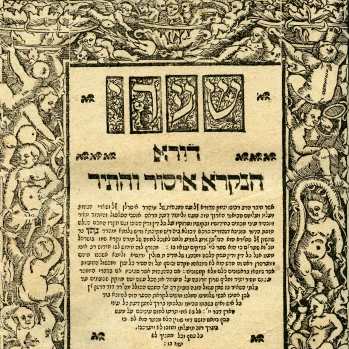

"Sha’are Dura" (The gates of Düren), 16th c.

Sha’are Dura (The gates of Düren) is a handbook that explains the finer points of kashrut. Rabbi Isaac Duren wrote it in the 13th century. In 1534/35, it was printed by the Helicz brothers, the first Jewish printers in Poland.

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews

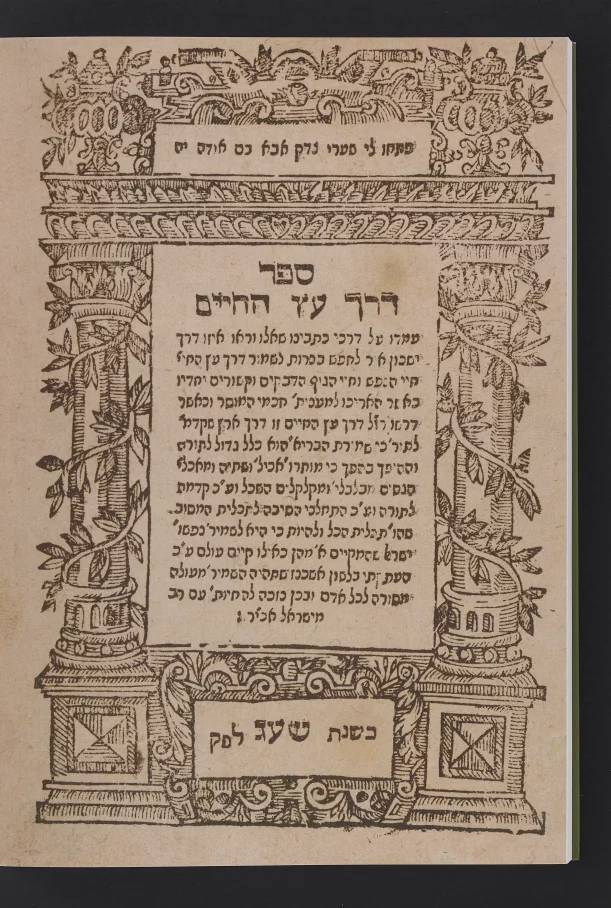

"Sefer derekh etz ha-haiym" (Guide to the Tree of Life), 1613

A medical treatise written in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth by an anonymous Jewish doctor. Following Arabic and Greek medicine, the author sees diet as an important factor affecting a person's health and mental condition; the customs he describes are strongly rooted in the local climate and culture of the Commonwealth.

Österreichischen Nationalbibliothek, Vienna

Landscape with a tavern

From the 16th century onwards, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was home of the largest Jewish diaspora in Europe. Jews played a vital role in local economy—working for royal or magnate estates, they acted as sales agents or leaseholders of various goods, such as mills, fish ponds, forests or taverns. A particularly important source of income in noblemen's estates was the production and sale of alcohol. It was especially important after the collapse of international grain trade in the 17th century. The nobility generally entrusted the running of taverns to Jews—until as late as the 19th century, Jewish taverns remained a mainstay of Polish village life.

"Scene in a tavern"

Kazimierz Żwan, steel engraving, 1818.

National Library in Warsaw

See related objects

"Polish Jewess – a lessee"

Jan Piotr Norblin (after Louis Philibert Debucourt), aquatint, first half of the 19th c.

POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews

Jewish tavernkeepers

Glenn Dyner, historian, talks about the role Jews played in the distillation of spirits, about Jewish tavern keepers in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and about the stereotypes connected to them.

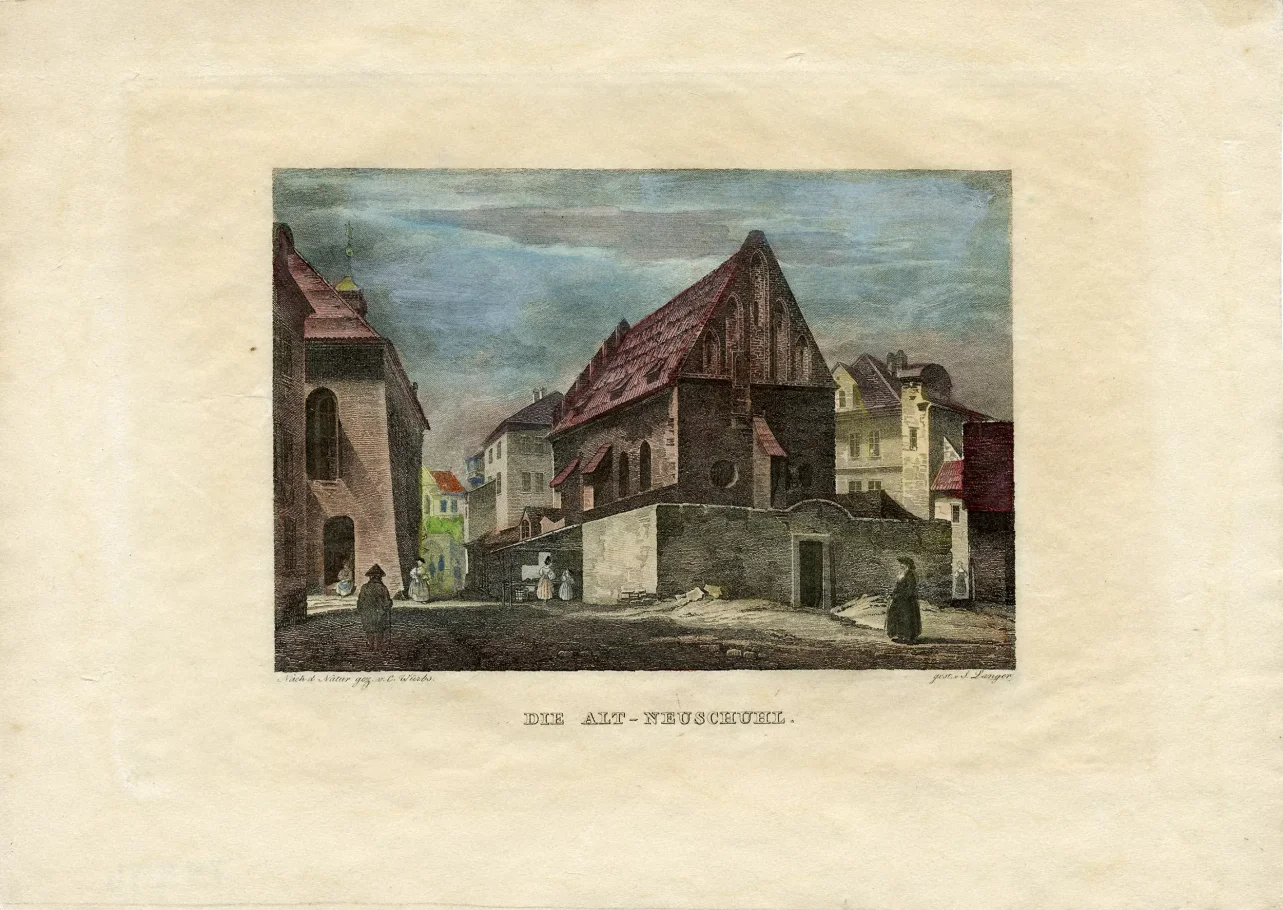

"Staronov synagogue in Prague"

Carl W. Würbs, 1845. Staronov synagogue in Prague (13th c.) is one of the oldest preserved synagogues in East-Central Europe.

Jewish Museum in Prague

In the Habsburg Empire

Jews in East-Central Europe also resided in the territory of the Habsburg Empire (present-day Austria, Czechia, Slovakia, Romania and Hungary). Under the influence of local culinary traditions, Jewish cuisine incorporated kosher sausages, salami, sauerkraut, potato salad, schnitzel, goulash, stuffed peppers, apple strudel and doughnuts with filling. With time, doughnuts became a traditional Jewish meal served on Hanukkah. Ashkenazim drew much inspiration from the baking traditions of Vienna and Budapest.

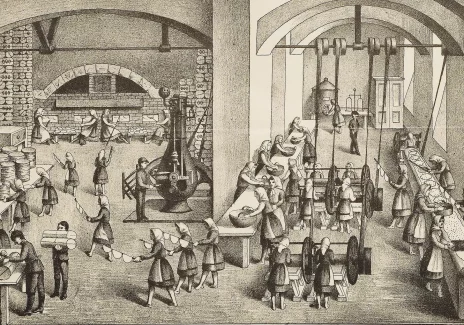

Production hall of the first matzo factory in Vienna

Illustration from an advertising leaflet, c. 1900

Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv

SCROLL or CLICK&HOLD

to go on